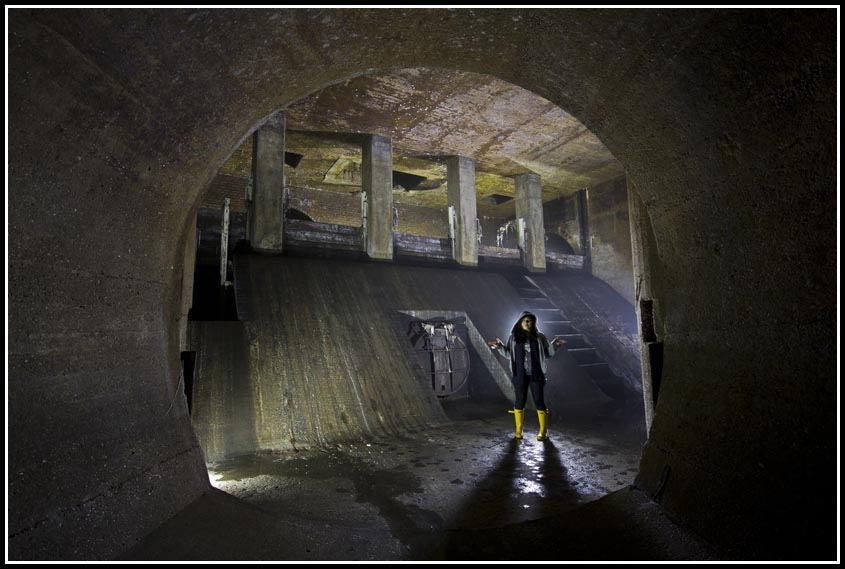

If you haven’t worked it out by now, i like the subterranean. Escaping the hustle & bustle above, strolling undetected beneath the sleepy metropolis through a sprawling maze of pipes and tunnels. Sewers, to me are epitome of this escape, the furthest point in which you can distance yourself from interaction within a city.

For many like myself, sewers and drains represent a photographic adventure, a potential to capture and present the unknown to the unaware. Some see them as a journey into the past, a historical and architectural look into the inner workings and operations of the city above. While for others its much simpler, an arena for social interaction, a space to party, meet those like minded, or just let time pass by.

Sadly however, those above are but a slim majority of the populous, those able to take advantage of this forgotten space. The public outside this small niche envision them only as sewage filled tunnels, nothing more, their interest ending when they pull the chain.

This brings us, aptly enough, to Félix Nadar (1820-1910). Nadar, a portrait photographer from Paris, in my view, shared similar opinions and views to those of us who explore sewers today. Sewers, for him, were not just tunnels buried underground, but avenues for experimentation within the art of photography. During 1864-65, using electrical light, Nadar created a collection of photographs of the parisian sewer system, some featuring dummy’s mocked up as workers due to the 18 minute exposure times needed. When these images were displayed to the curious french public they “intrigued and astounded”. A world unknown, or misinformed to them, revealed before their eyes.

This brings us, aptly enough, to Félix Nadar (1820-1910). Nadar, a portrait photographer from Paris, in my view, shared similar opinions and views to those of us who explore sewers today. Sewers, for him, were not just tunnels buried underground, but avenues for experimentation within the art of photography. During 1864-65, using electrical light, Nadar created a collection of photographs of the parisian sewer system, some featuring dummy’s mocked up as workers due to the 18 minute exposure times needed. When these images were displayed to the curious french public they “intrigued and astounded”. A world unknown, or misinformed to them, revealed before their eyes.

“…Paris has another Paris under herself; a Paris of sewers; which has its streets, its crossings, its squares, its blind alleys, its arteries, and its circulation, which is slime, minus the human form.” - Les Misérables

Like many european cities, the parisian sewer system was established around a pre-existing medieval network of ditches, tunnels and cesspits in its center. A network which, for a time, served its purpose. It wasn’t until the 1800′s, as attitudes to public hygiene and the disposal of bodily waste changed that the system grew insufficient.

In June of 1853, Emperor Napoléon III appointed Baron Georges-Eugéne Haussmann (1809-91) with the task of “modernising” Paris. This entailed the construction newer, safer streets, better housing and improving the sanitary conditions of the city. In August of 1853, Haussmann appointed Eugéne Belgrand (1810-78) as overseer of the sewer systems reconstruction. However It wasn’t until 1857 that the reconstruction of the paris sewers kicked into gear. This included work on construction a newer, larger collector “Général D’asinéres”, primarily designed to alleviate the pressure of rainwater from the system, discharging into the Seine downstream of the city. By 1870 the sewer network had grown to almost 348 miles of tunnels.

In June of 1853, Emperor Napoléon III appointed Baron Georges-Eugéne Haussmann (1809-91) with the task of “modernising” Paris. This entailed the construction newer, safer streets, better housing and improving the sanitary conditions of the city. In August of 1853, Haussmann appointed Eugéne Belgrand (1810-78) as overseer of the sewer systems reconstruction. However It wasn’t until 1857 that the reconstruction of the paris sewers kicked into gear. This included work on construction a newer, larger collector “Général D’asinéres”, primarily designed to alleviate the pressure of rainwater from the system, discharging into the Seine downstream of the city. By 1870 the sewer network had grown to almost 348 miles of tunnels.

However, this new system was not without its problems. Haussmann had always strongly opposed the mixing of rainwater and human waste within the new network, choosing to construct a separated system of storm and sewage tunnels. His decision based upon the amount of sewage entering the system at the time. Hausmanns modernisation of Paris had led to the demolision and removal of the parisian slums for newer housing, the former of which disposed of waste via cesspits. The newer housing however, were connected directly into the sewer network, contributing additional water and waste.

In 1894, connections to the network from private households were made mandatory, Hausmanns separated system could no longer cope with the extra waste, mostly stemming from the increasing use of water for hygiene purposes. The storm sewers eventually forced to accommodate human waste.

Exploring sewers in different countries, you tend to notice little differences. The sewage networks of Paris and London, although serving the same function, to me, couldn’t be more apart. On one hand, you have London. Joseph Bazalgette, photogenic brick tunnels, culverted rivers and the interceptors that serve them. The essence of Victorian over- engineering and pride visible in every tunnel. Contrary to that, the parisian network feels somewhat empty. Cold, emotionless concrete under every manhole. A mess of tunnels and pipes darting in every direction. A network built to serve its function and nothing more. Bland, yet rewarding the visitor with an alternate experience.

Exploring sewers in different countries, you tend to notice little differences. The sewage networks of Paris and London, although serving the same function, to me, couldn’t be more apart. On one hand, you have London. Joseph Bazalgette, photogenic brick tunnels, culverted rivers and the interceptors that serve them. The essence of Victorian over- engineering and pride visible in every tunnel. Contrary to that, the parisian network feels somewhat empty. Cold, emotionless concrete under every manhole. A mess of tunnels and pipes darting in every direction. A network built to serve its function and nothing more. Bland, yet rewarding the visitor with an alternate experience.

London’s main downfall is the lack of navigational challenge, its layout too simple, most sections consisting of only one or two walkable tunnels. The parisian network, isn’t. Give a child some paper and a set of multi-colour crayons, the resulting image would be similar to its sewer map. Adventure in Paris rests, not in taking photographs, but by traversing the city, getting lost under it, truly experiencing it, finding routes and discovering crossover’s to other sections of its infrastructure. Never before have i entered a sewer and found myself sitting under a bridge, boats driving underfoot five minutes later, without exiting the system. Paris is just different, but in a good way!

London’s main downfall is the lack of navigational challenge, its layout too simple, most sections consisting of only one or two walkable tunnels. The parisian network, isn’t. Give a child some paper and a set of multi-colour crayons, the resulting image would be similar to its sewer map. Adventure in Paris rests, not in taking photographs, but by traversing the city, getting lost under it, truly experiencing it, finding routes and discovering crossover’s to other sections of its infrastructure. Never before have i entered a sewer and found myself sitting under a bridge, boats driving underfoot five minutes later, without exiting the system. Paris is just different, but in a good way!

Dates and Nadar Photograph thanks to Matthew Gandy

I would really enjoy to see what kind of things you would find in there, because the whole thing connects with sewers and the “metro” network. It was used by the resistance durin the world war, and used as a cemetry for the “catacombe” part, which was a huge network of quarries. Just be carfull if you go there because the police is checking the accesses, but i’m sure you can find reliable maps of the whole thing. It was a hobby for some people to get there in the 80′s, but after several accidents, the police became more carefull.

Reply

Great pics and story

Reply

I live in N. Texas and there is nothing like that !!! I am so excited to doscover

this on

the web.

Reply