At its core, the act of exploring a sewer, is a pretty disgusting affair. It comes with all the negative aspects you would expect from such an activity, faeces, urine, blood, tampons, grease, toilet roll, all the content you expel from your home or place of work on a daily basis, banishing them to a place where they are no longer your concern. What many fail to realise, or choose to simply ignore, is that several positives exist within a sewage system, be that of a historical, architectural or even photographic nature.

Even with the pictures we bring back and the stories we tell, many just can’t seem to wrap their heads around this idea, always coming back to one point, that we walk around in peoples excrement. This at its fundamental level differentiates sewer explorers from others, we choose to look past this one nasty fact, in our minds the positives and reward outweigh the negative and nasty. To a certain degree, It’s why I tend to omit this particular aspect of the hobby when I explain what I do in my spare time. If the subject is brought up, I usually say I climb things, you tend to get less disgusted looks that way. End of the day, your mind is likely already made up, if the content sewer explorers create isn’t enough to change your mind, nothing will be.

While it’s true that many of London’s “Lost Rivers” and sewers are combined, meaning they contain both rain water and sewage, most tend to lean more towards the latter. The Ranelagh Sewer, aka The River Westbourne / Kilburn is slightly different in this respect. This is down to a number of reasons, frequent interception, diversion, minimal interaction with smaller foul sewers, partial alternation of its mainline into a storm relief and construction of an infall from the Hyde Park Serpentine. As a result the majority of the middle and lower sections of the system are much more hospitable than that of say the Effra or Fleet. Although falling over would still cause an early end to the night, the chance of returning to your feet with brown and red content stuck to your face is greatly reduced.

The Ranelagh for many, myself included, is where their adventures into sewer exploration truly began. It’s mixture of large diameter tunnels, array of features, relatively clean waters and historical significance to the area are more than enough to attract even the most cautious of sceptics.

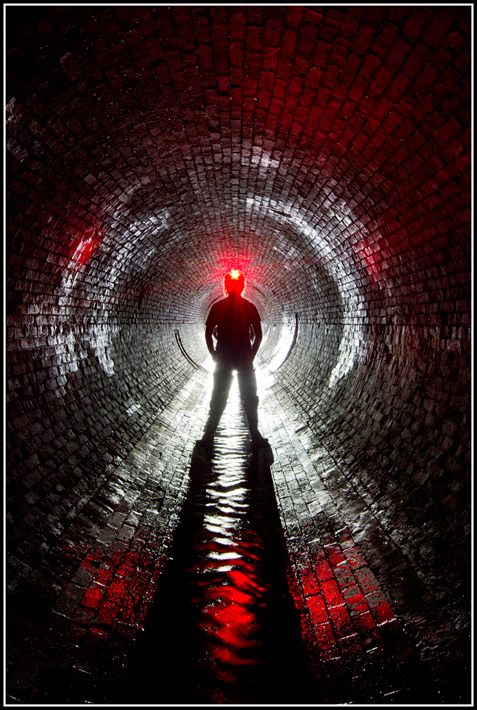

Ranelagh Storm Relief Sewer . Left - Serpentine Infall . Right - Tyburn Brook

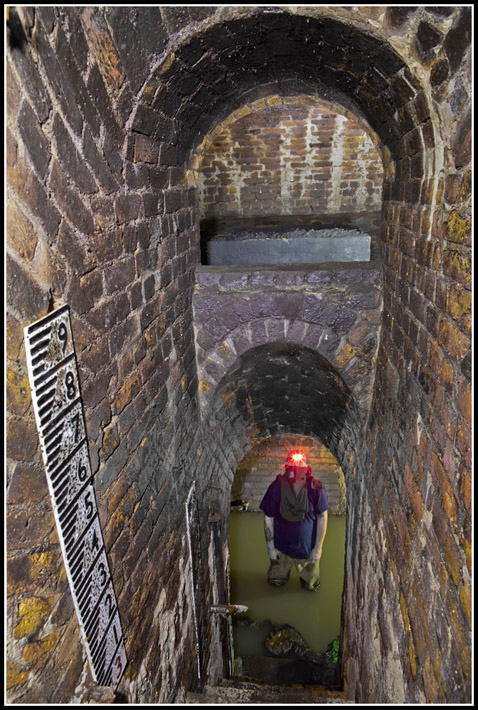

The Westbourne originally rose in Hampstead, North London, flowing through Kilburn, Bayswater, Knightsbridge and Chelsea to its terminus with the River Thames at Ranelagh Gardens. In 1730, at the instigation of Queen Caroline, wife of George II, the river was dammed at Hyde Park in order to “beautify” the area. This process flooded the marshy areas of the royal park and the Serpentine was formed. Unfortunately the rivers flow was not enough to efficiently support a body of water that size, heavy rainfall the only remedy to the lakes often stagnant water.

Even so, the Serpentine was frequently used for bathing, which unfortunately, lead to many deaths. As the lake was nothing more than flooded marshland, a thick layer of sludge existed at the bottom, sticky enough to trap and drown those who became entangled in it. This combined with the fact that mere mouthfuls of the water often proved fatal resulted in 117 deaths in just 15 years, 88 of those were reported as suicides.

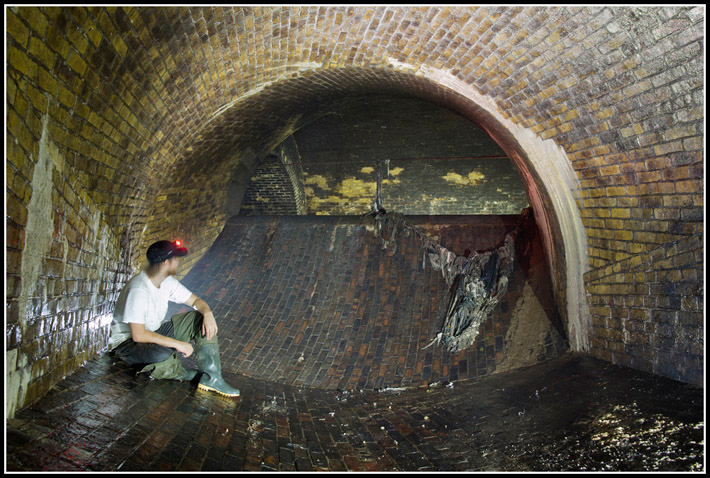

Serpentine Infall Chamber

By this time the Westbourne, now named the Ranelagh Sewer due to its pollution, had ceased functioning as supplier to the Serpentine, the lakes contents now pumped directly from the Thames. The Ranelagh Sewer instead had been diverted east in 1834, from Lancaster to Albion gate where it joined with the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the Westbourne. Now combined, the two flowed the Tyburn Brooks partially open course until rejoining the Ranelagh’s original course just south of the Serpentine.

This was not the only work to have taken place around this time. Major developments in the Chelsea, Paddington and Belgravia area had required additional space to proceed. This requirement for space, meant the Ranelagh needed to be covered. Work covering the sewer began in 1827 and it wasn’t until 1854 that the project was completed, the Ranelagh now enclosed for the majority of its course.

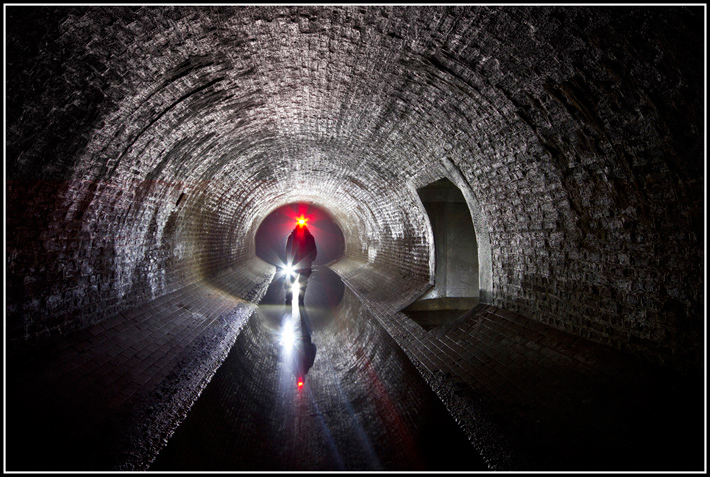

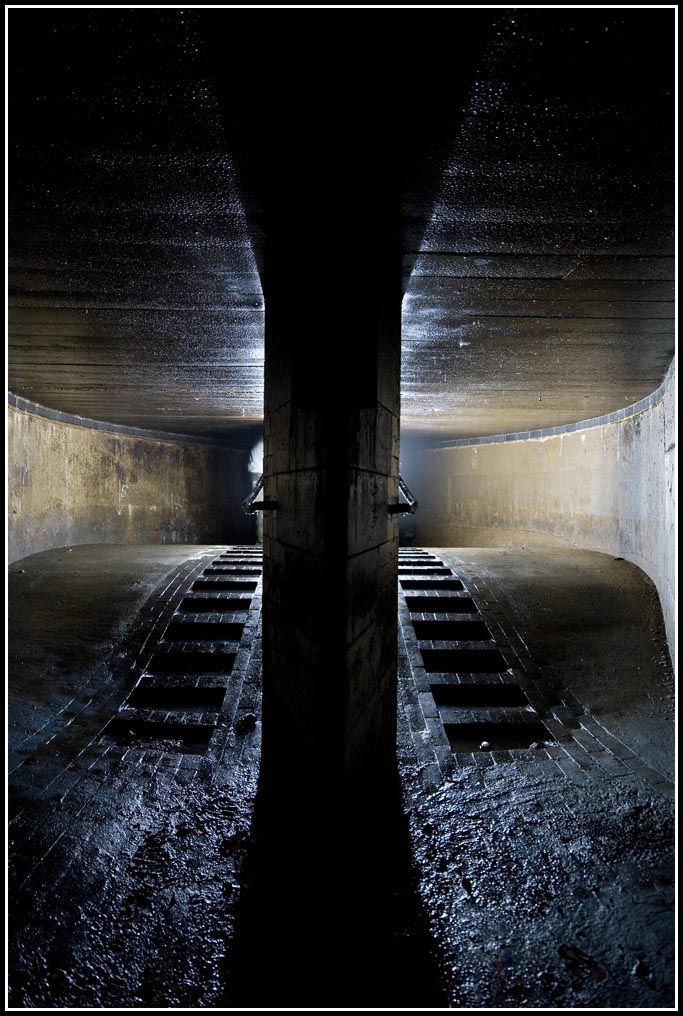

Ranelagh Storm Relief Sewer Rejoins Ranelagh Sewer (Looking Upstream)

Although enclosed, alternations continued. After the outbreak of two Cholera epidemics that killed almost 25,000, Joseph Bazalgette (Sir), who had served on the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers during this time, was appointed Chief Engineer of the newly formed Metropolitan Board Of Works in 1856. He was tasked with creating a solution to the Cholera issue, which, at the time was believed to be transmitted by foul air, a “miasma”. The majority of fingers pointed to London’s cesspit’s and open sewers as the cause, and as a result, Bazalgette’s sewage and interceptor plan, which after years of rejection, was finally accepted in 1859.

Bazalgette’s plan, as far as the Ranelagh was concerned, resulted in two interceptors being driven across its course at Bayswater and the Chelsea Embankment. Each of the interceptors were designed for the sole use of carrying the contents of each interacting sewer to the Abbey Mills pumping station in East London (Crossness for South London). This system of interceptors would prevent, or reduce the amount of raw sewage flowing directly into the Thames. The exception to this was in the event of heavy rain and flooding.

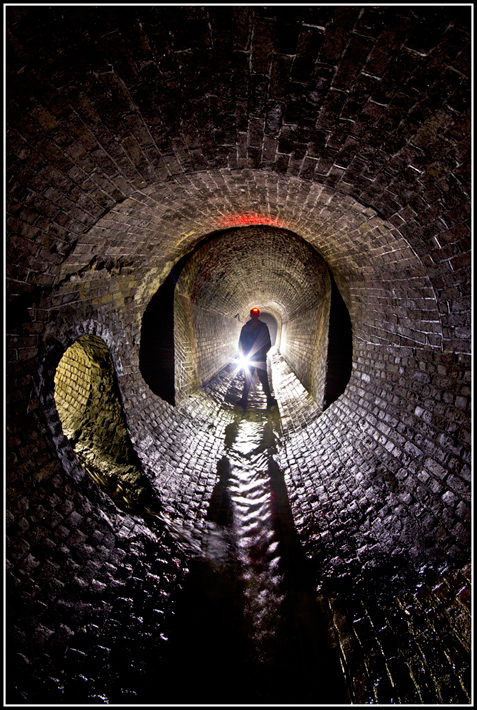

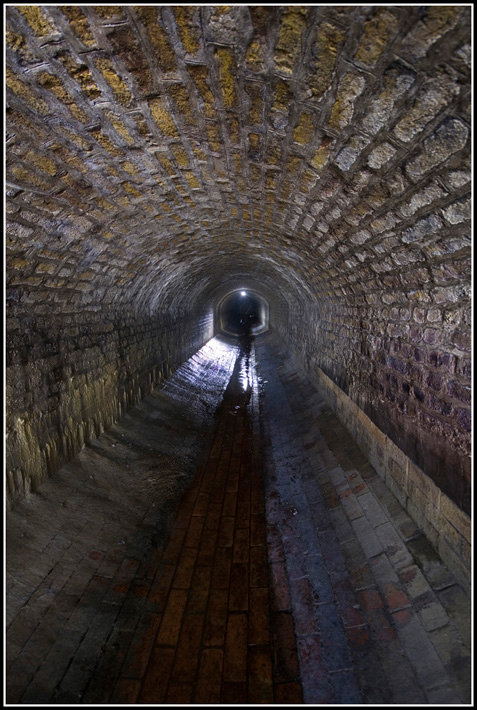

Ranelagh Sewer , Tunnel Depth Increased To Match The Middle Level Sewer No*1 (Looking Upstream)

While this plan had an impact on the entire Ranelagh system, its effects are most visible in the area around Hyde Park. The construction of the Middle Level Sewer No*1 (1861-1864), resulted in the alteration and overall abandonment of the diversion to the Tyburn Brook. The Middle Level was constructed deeper than the current Ranelagh Sewer, this was in order to meet the overall west to east gradient required to ensure the flow kept pace until Abbey Mills. As a result the Ranelagh Sewer had to be dropped over 30 feet to allow a connection. While tumbling bays or drop shafts are usually used to achieve this task, here a slide was constructed, something I believe is unique in the London sewer system.

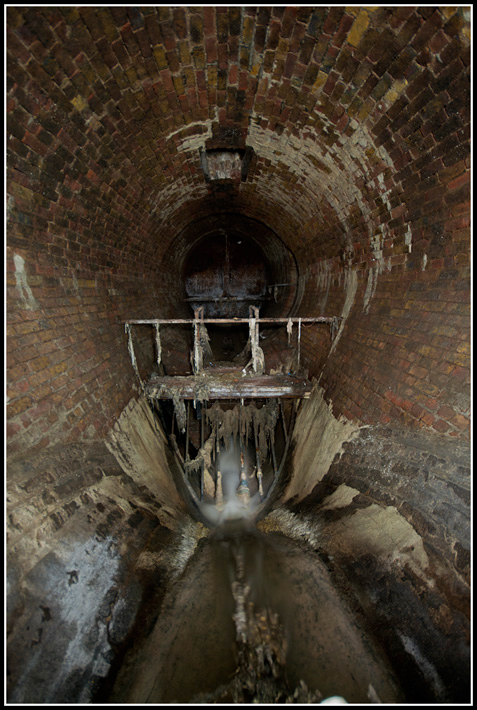

Lowered Ranelagh Sewer , Original Ranelagh Sewer (Disused) Above

This section, in my opinion, holds the Ranelagh’s best kept secret. For sitting atop the newly constructed sewer is a short stretch of tunnel that would have once fed the Serpentine and latterly the 1834 diversion. Now defunct and bricked at both ends, It serves no greater function beyond providing ventilation, a reminder from its former existence that escaped demolition.

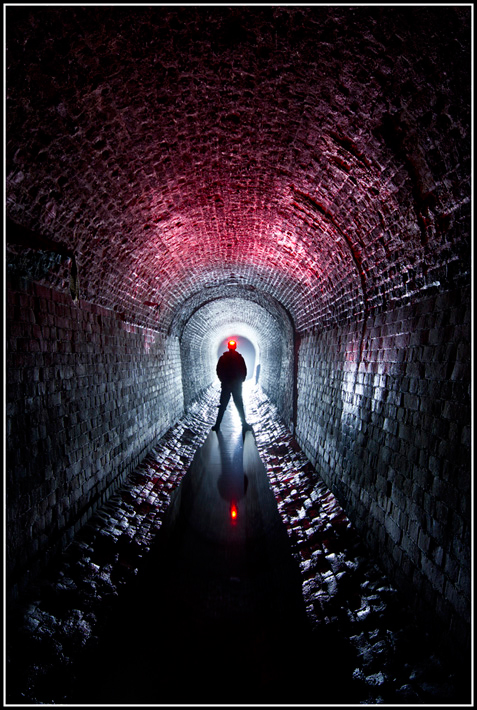

Ranelagh Storm Relief Sewer - West Branch (1886) , Ranelagh Sewer Overflow.

Ranelagh Storm Relief Sewer - West Branch (1886)

Prior to this, the Tyburn Brook, now containing the diverted Ranelagh Sewer, had long since reached its limit, flooding the streets several times as a result of increased strain from nearby developments. It would simply be unable to cope with the extra flow a new interceptor would bring in the event of a storm. As a result to ease the pressure, the Ranelagh Storm Relief Sewer (1860-1862) was also constructed. The relief flowed a similar course as its name sake, flowing from a weir with the Middle Level Sewer No*1 at Bayswater, through Hyde Park to the junction of the Serpentine infall and Tyburn Brook, before continuing to the southern border of the park where it rejoined the formerly covered tunnel. A secondary weir was constructed in 1886 to further alleviate the pressure.

Left - Ranelagh Sewer , 1834 Diversion (Disused) . Right - Tyburn Brook

Tyburn Brook , Middle Level Sewer No*1 Overflow

Ranelagh Sewer , 1834 Diversion (Disused)

Here’s where things get harder to explain. On paper, this sounds logical enough, but in person, when you’re actually standing in the tunnels looking at what is described above, its sometimes hard to connect the dots. This, in essence, is thanks to works carried out in the early 20th century by the London County Council (1889–1965). This new body took over the duties held by by the Metropolitan Board of Works which was abolished in 1889, It was also at this point that Bazalgette retired, dying two years later at the age of 71.

Ranelagh Storm Relief Sewer. Left - West Branch (1886)

Ranelagh Storm Relief Sewer, Ranelagh Sewer Overflow.

The L.C.C under the guidance of Chief Engineer Alexander Binnie (1839–1917), succeeded in 1901 by Maurice Fitzmaurice (1861-1924), were largely responsible for the construction of the red brick storm relief’s that litter this, and other sewer exploration sites. Not Joseph Bazalgette and the Metropolitan Board of Works as I once believed. This work also included construction of new interceptors and pumping stations, as well as the reconstruction and reconditioning of those existing to further strengthen the system.

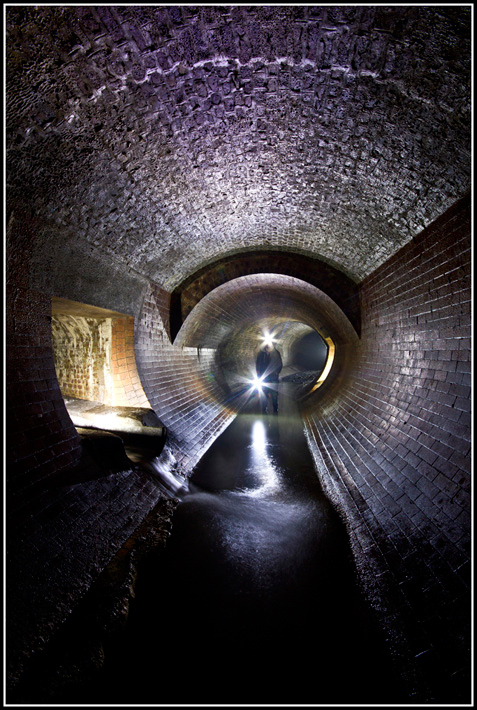

Ranelagh Storm Relief Sewer Rejoins Ranelagh Sewer . Right - Ranelagh Storm Relief Overflow (1884-86 , The Egg)

Ranelagh Storm Relief Sewer , Ranelagh Storm Relief Overflow (1884-86 , The Egg)

In terms of North London, the sewer projects of the L.C.C resulted in the addition of the Middle Level Sewer No*2 (1906-11) and Low Level Sewer No*2 (1904-1912), with connections from the Ranelagh being built at Westbourne Green and Belgravia respectively. More importantly, as far as I am concerned, it meant the construction of the North Eastern (1921-5) and North Western Storm Relief’s (1925-8), architectural and photographic pleasures.

Little has changed since these works by the London County Council, what is left of the river now running silent, completely hidden from view. Its only public appearance when floods force the waters to burst into the Thames, something which will continue until Thames Water, the current governing body and holders of the keys to the London sewage system, complete work on their new, £4.1 billion, Thames Tideway tunnel. The future of London’s underbelly, although certainly not beautiful, will certainly be interesting!

Ranelagh Sewer , Overflow With The Western Deep Sewer , 1992-1994

Ranelagh Sewer , Flow Control Gate

Awesome!

Reply

This is great. Sad to think that so much engineering is hidden from the public and will never get the recognition it deserves..

Reply

Wow wow wow, you guys are brilliant. I would love to see, just amazing.

Reply

A unique contribution to cultural knowledge. What pleasure you’ve given us: a thousand thanks!

Reply

Excellent! Very-very interesting, guys!

Reply

Great exploration and photos!

Reply

Great to see a post after such a long absence, and a fine one it is too. Hope you’re managing to still get out as often as you’d like. Really inspiring stuff.

Reply

So dope!

Reply

Excellent stuff. Thanks for this.

Reply

Brilliant stuff, enjoyed the history as much as the photos - wish I knew some people in Lon, getting bored of doing flooded mines now tbh !

Reply

Nice one Otter. The second and third images are absolutely bloody stunning!

Reply

Class that is boss

Reply

Another brilliant post! I find it fascinating that there’s all of this architecture and feats of engineering underground that we never get to see! Hot it’s managed to stand the test of time I don’t understand but it’s amazing!

Reply

beautiful

Reply

you guys are brilliant! i envy you lot.

Reply